THUS SPOKE MY OLD MAN !

Welcome to the Idle Words Said in Passing

A PHILOSOPHY OF MORALS - IMMANUEL KANT!

Practical Thoughts, a moral dimension.

Is your life a life of peace and tranquillity ? Do you live in harmony and peace with other people?

We are social animals. We need other people, but, how to live with others without conflict?

One can be very practical about that. German philosopher Immanuel Kant can help us here. He formulated some principles and maxims which can guide your moral decisions in the most practical of ways.

Let me give you an example and a suggestion how to apply it in your daily activities.

In his Metaphysics, Immanuel Kant introduced the categorical imperative:

"Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law."

To put it simply this means: What if everybody else did the same?

Look at yourself when on the road driving a motor car. Do you exceed a speed limit from time to time and willingly so? Are you quite ready to forgive yourself such an infringement? But, ask yourself another question:

What if everybody else would do the same?

Everybody speeding on the roads ? That would not work well!

Imagine lending some money to a friend who is not willing to pay it back. That would not work either. In addition the lending and borrowing concept would make no sense any more.

Hey, hey ... this is such a simple question to guide you in your decision making.

The way Immanuel Kant formulated his categorical principles is much more complex.

Here it the more detailed treatment of Kant's Categorical Imperatives. Enjoy!

First formulation:

Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.

It is Kant's view that a moral proposition, if true, must be one that is not qualified by any specific conditions, such as the identity and wishes of the person making the moral deliberation.

A moral maxim must be disconnected from the particular physical details surrounding the proposition, and could be applied to any rational being. Thus, the first formulation of the categorical imperative is known as the principle of universalizability: - "Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law."

Here we can see a close connection of this formulation and the law of nature formulation. It is generally accepted that the laws of nature are universal. Kant suggested that we may also reconstruct this categorical imperative as: "Act as if the maxims of your action were to become through your will a universal law of nature."

Kant divides the duties arising out of this formulation into two sets:

The first division is between duties that we have to ourselves versus those we have to others.

Kant determined that we first have a perfect duty not to act by maxims that result in contradictions when we attempt to make them universal in application.

In an example a proposition A: "It is permissible borrow money without intention of paying it back!" This would result in a contradiction upon universalisation. The concepts of borrowing would make no sense at all, and as such when a proposition if applied universally would negate itself.

In general, perfect duties are those that are culpable / blameworthy, if not met, as they are a basic required duty for a human being.

Kant determined that we first have imperfect duties, based on pure reason, but which allow for desires when these are carried out in practice. These depend somewhat on the subjective preferences of humankind. Imperfect duty is not as strong as a perfect duty, but it is still morally binding.

It is getting complicated ... To enjoy reading about the second formulation scroll down to next box.

Second formulation: Humanity

Formula of the End in Itself: --

Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.

The second formulation of the categorical imperative is called the Formula of the End in Itself. Every rational action must set before itself not only a principle, but also an end.

Most ends are of a subjective kind, because they need only be pursued if they are in line with some particular hypothetical imperative that a person may choose to adopt. For an end to be objective, it would be necessary that we categorically pursue it.

The free will is the source of all rational action. But to treat it as a subjective end is to deny the possibility of freedom in general. Because the autonomous will is the one and only source of moral action, it would contradict the first formulation to claim that a person is merely a means to some other end, rather than always an end in themselves.

In other words, we should not use people as objects, but instead recognize the inherent dignity and value that we all have. It helps to understand Kant's point if we distinguish between things that have merely instrumental value and things that have inherent value.

On this basis, Kant derives the second formulation of the categorical imperative from the first.

By combining this formulation with the first, we learn that a person has perfect duty not to use the humanity of themselves or others merely as a means to some other end.

One cannot, on Kant's account, ever suppose a right to treat another person as a mere means to an end. In the case of a slave owner, the slaves are being used to cultivate the owner's fields (the slaves acting as the means) to ensure a sufficient harvest (the end goal of the owner). Or, for that matter, this should apply to unscrupulous employers using workers as, merely, means to employer's end.

The second formulation also leads to the imperfect duty to further the ends of ourselves and others. If any person desires perfection in himself or herself or others, it would be his or her moral duty to seek that end for all people equally, so long as that end does not contradict perfect duty.

-edited.jpg)

Third Formulation: -- Autonomy

Thus, the third practical principle follows {from the first two} as the ultimate condition of their harmony with practical reason: the idea of the will of every rational being as a universally legislating will.

Kant determines that the first formulation proposes the objective conditions on the categorical imperative: that it be universal in form and thus capable of becoming a law of nature.

The second formulation proposes subjective conditions: that there be certain ends in themselves, namely rational beings as such.

The consequence of these two considerations is that we must will maxims that can be at the same time universal, but which must not infringe on the freedom of ourselves or of others.

A universal maxim, however, can only have this form if it be a maxim that each subject by himself accepted. Because it cannot impose external constraints on subject's activity, it must be a constraint that each subject has set for himself. This leads to the concept of self-legislation. Each subject must through his own use of reason will these maxims to have the form of universality, and not obstruct the freedom of others.

Therefore, each subject must will maxims that could be universally self-legislated.

This third formulation makes it clear that the categorical imperative requires autonomy. It is not enough that the right conduct be followed, but that one also demands that conduct of oneself.

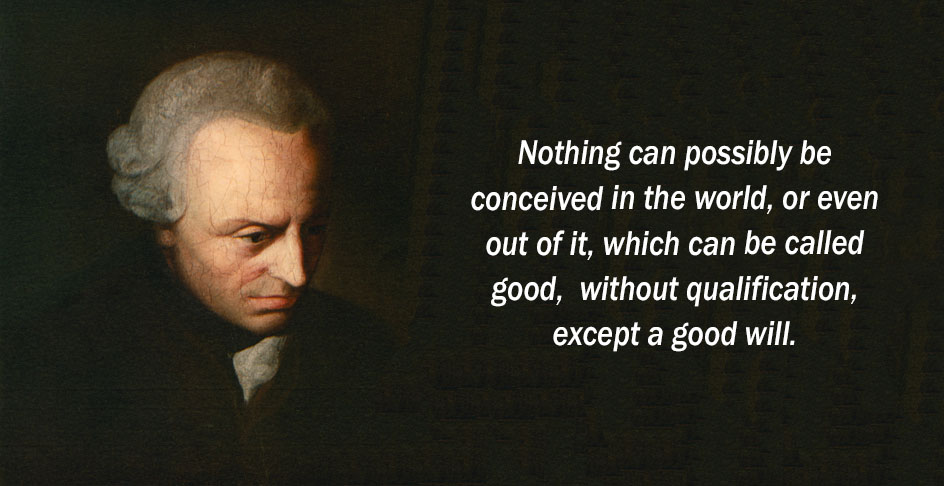

Kant's discourse on Goodwill is a central concept in his moral philosophy.

.

Kant's discourse on Goodwill is a central concept in his moral philosophy.

.

According to Kant Goodwill is the only thing that is good without additional qualification. Whilst qualities such as courage or intelligence are good only with qualifications and can be used for evil, Goodwill is good in and of itself. It does not depend on the consequences of an action; it's depends on the motivation behind it. Goodwill is the ability to act purely out of a sense of moral duty rather than from self-interest or desire.

Intrinsic Value of Goodwill is that the Goodwill is the only thing that is good without reservation or the qualifications. Its value doesn't depend on what it achieves; it's valuable in its own right because it comes from a commitment to do what is right.

Looking at this painting we can feel a surprise and quite some incongruity. An incongruity of wise words of a philosopher and a strange clothes and environment in which they were created, produced and discussed. We do not wear their clothes any longer, yet we still use those words of wisdom. Beware of anachronism! It is ready to trip you as you walk along with them.

NAVIGATION BAR

The Thinkers Menu!

-

Return to Home Page

Return to Home Page

The Menu Guide to Other Philosophers is on Home Page

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant, (22 April 1724 - 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics have made him one of the most influential figures in modern Western philosophy.

Important Message

Starting to read Immanuel Kant ?

But, where to start?

Read this first !

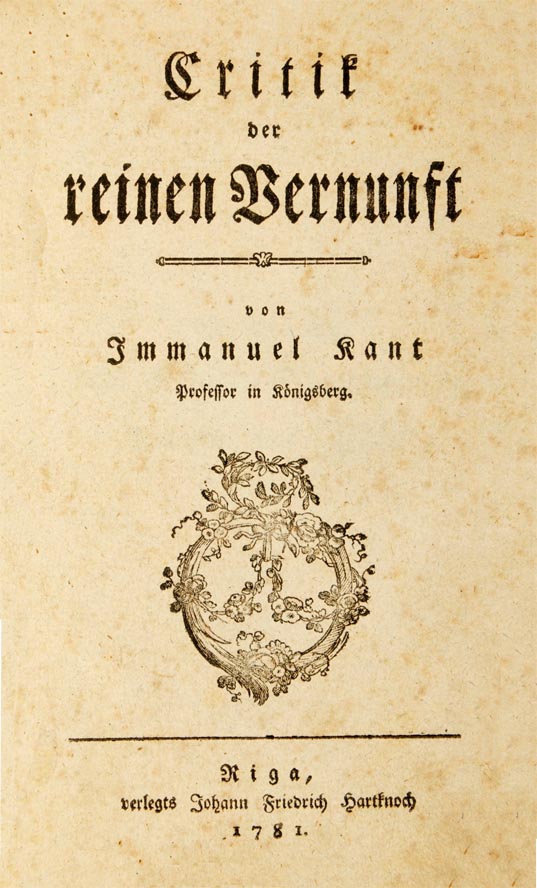

It has been said that a good introductory book to philosophy should be Kant's The Critique of Pure Reason. Surprisingly, at first, this seems laughable and almost absurd: Kant's texts, especially his later works, are notoriously difficult to read, His dense prose intimidate those who try and sometimes terrify even seasoned readers.

Yet, this suggestion had a point. Once you find a way into reading Kant, his texts can teach you how to think well and in an organised and structured way. All his books and particularly "The Critiques" are satisfyingly complex, systematic, critical, and are stimulating you to wrestle and disagree with them

So, where should you start? It helps to know a little about Kant's background, his interests, his way of thinking, and the concepts he uses. Once you crack the code to reading Kant, his works become the ultimate teaching aid in learning how to think deeply and critically. Kant challenges you, forcing you to engage, to disagree, and think in systematic and profound way. So, where do you begin? It helps to explore Kant's background, his motivations, his distinctive way of reasoning, and the key concepts that frame his thought. I shall be brief.

Immanuel Kant, the fourth of nine children, was not born into wealth and privilege like many of the great Enlightenment philosophers we still celebrate today. His father, a bridle maker, held a tradesman position far beneath that of a saddler in terms of both economic and social status. The Kant family adhered to Pietism, a 17th-century religious movement aimed at revitalizing Protestant life and reforming the church.

Kant was not religious in his adulthood, a fact well known to his community, and as a result many have accused him of contributing to the decline of church attendance in Königsberg.

Notwithstanding his religious doubts he always valued the inner peace and positive outlook that the Pietist way of life had instilled in him, which he thought similar to the Stoic philosophy. Kant often credited his mother's 'natural' rational thinking and strong moral principles as early influences that shaped his worldview.

Kant's community recognized his intellectual capacity. Collectively they helped Kant attend a prestigious, though rigid school. Notwithstanding such rigid classical education Kant's intellectual curiosity endured.

He later enrolled at the university, supporting himself through tutoring and winning at billiards, a skill that helped him sustain himself throughout his younger years. So, there you are, a little bit of trivia. At 46, Kant was appointed a professor in Logic and Metaphysics University of Königsberg, which not only fulfilled his academic aspirations but also brought him financial stability.

Immanuel Kant spent his entire life in Königsberg, a bustling commercial centre of Prussia during his time. His circle of friends, colleagues and student was diverse. They came from various regions: Prussia, German states, Russia, the Baltic, Poland, and others.

Despite his dedication to his work at the University, Kant spent the second half of each day for socializing: meeting friends, playing billiards and cards, attending salons, and visiting the theatre. Such was his flamboyant social life. Well, maybe he was not such a dull boy, but open to enjoyment of comforts and indulgences.

Kant was at the forefront of both natural sciences and metaphysics. In 1755, he anonymously published "The General Natural History and Theory of the Heavens," in which he proposed a purely mechanical explanation for the origin of the universe.

At the same time King Friedrich Wilhelm II, had reintroduced stricter measures, leading to Kant's trouble with censors. There were rumours abound that Kant might be exiled or at least silenced, losing the right to publish or teach. Although this did not happen, Kant received a stern warning from the King himself, accusing him of abusing his position as an educator to turn young minds against the Church's teachings. Unintimidated, Kant promised not to publish any more writings on religion as long as the King lived. Well, maybe he was not such a dull boy, but rebellious as well.

The Three Critiques

Why are Kant's famous three "Critiques" known as such? What are they critical of, and why? They are a critical reflection on the limits of the application of reason, and at the same time, of Kant's own philosophical tradition. Kant was educated in the tradition of Rationalism, and in particular, the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz and Christian Wolff. Rationalists believed that knowledge stems from reason. Although Kant had harboured doubts about this foundational belief long before his "Critiques" period, it was his reading of David Hume that fully awakened him from his "dogmatic slumber."

Kant used the term "dogmatism" to critically describe Rationalism and referred to Hume's Empiricism as "Scepticism." While Rationalists believed knowledge originates in reason, Empiricists contended that it stems solely from experience. A key distinction is between "reason" and "understanding." Reason is the ability to think logically - it is not about intelligence or education. Though reasoning skills can be developed, Kant maintained that reasoning is a universal human capacity, meaning everyone is capable of thinking rationally and that nobody can be excused from thinking rationally. It means being able to infer a conclusion from reasons and to avoid fallacies such as holding mutually contradictory beliefs. So, 'reason' is what we use to think well; it is independent of experience.

In contrast, "understanding" pertains to how we make sense of the world around us and the "understanding" is inherently tied to experience. This distinction is also expressed in the terms a priori ("before experience") and a posteriori ("after experience").

Kant's central argument is that reason alone cannot provide knowledge. He argues that knowledge requires input from the external world, and it is through the interaction of reason with our senses and the world that we come to know things… Knowledge, for Kant, is a posteriori-based on experience. Attempts to gain knowledge purely through reason lead only to "darkness and contradictions."

It is in the field of ethics, covered in the Critique of Practical Reason, that "reason" really comes into its own: Kant believes that we employ reason to be free in our thinking about moral principles; they are a priori. However, in ethics, as explored in the Critique of Practical Reason, reason plays a crucial role. Kant believes that reason is vital for our moral freedom, as it allows us to think independently about moral principles, which are a priori.

Why are there three Critiques, rather than just two? The distinction between the Critique of Pure Reason and the Critique of Practical Reason is clear. In the first Critique, Kant explores the conditions necessary for acquiring knowledge. However, when considering moral values, it becomes apparent that moral reasoning operates differently from the way we understand the world through knowledge. This is the focus of the second Critique.

But what, then, is the purpose of the third Critique, the Critique of Judgement? It serves to bridge the gap between the two earlier Critiques. When reading the first two works, it is easy to see how the domains of sensory experience and moral reasoning - nature and freedom - seem disconnected. Judgement, however, is the human capacity that unites them. A useful example of this is aesthetics. An aesthetic judgment, such as "This rose is beautiful," differs from a statement of knowledge like "This rose is red." Yet, an aesthetic judgment also differs from a moral statement. Aesthetic judgements require both attention to the natural world, through sensory experience, and the exercise of human freedom, through subjective imagination.

Why are these Critiques so significant, and why do they continue to hold such significance and importance? Why did many consider the Critique of Pure Reason "the most important book ever written in European philosophy"? Was Kant right in everything he posits in the three Critiques? Of course not; or maybe not, if you will.

Was he right or wrong … that should neither be an expectation in our reading nor the right way by which to judge any philosophy.

For instance, many thinkers have justifiably criticized Kant's conclusion in the Critique of Practical Reason that morality is grounded in rules which each individual must freely choose and then universally obey, as encapsulated by the concept of the "categorical imperative" … no matter the situation.

Such highly formalised approach to ethics can be challenging or impossible to live by. Yet, Kant's perspective offers valuable insight into the nature of morality and moral reasoning, advancing philosophical discourse in a profound way. While we may find his ethical system difficult to follow in practice, we cannot disregard it in the broader study of moral philosophy, or, for that matter, in its application in our daily lives.

The same holds true for the Critique of Pure Reason, whose revelations fundamentally reshaped our understanding of metaphysics and epistemology. Finally, the Critique of Judgement makes groundbreaking contributions to the foundations of philosophical aesthetics, with insights that remain relevant today. Instead of expecting any philosophical work to provide final answers, it is more productive to see it as a contribution that opens new perspectives and expands the scope for further philosophical exploration. His work thus provides not merely a scope for an academic discourse, but also it opens new perspectives and the opportunity for exploration in practical everyday life.

Ready to start! Now that you have a basic understanding of Kant's background and projects, you are in a stronger position to begin reading his work, including even the challenging Critiques or, maybe you can start reading the famous but shorter: Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals.

Take it on slowly. Philosophy should always be read slowly and carefully, so patience is essential. Like many great philosophers, Kant encourages us to engage critically with his ideas, so be prepared to think actively and deeply as you read.

Ultimately, you can form your own judgment about the relevance of his contributions. But make sure to do so in an informed, thoughtful manner. Put in the effort - that's how Kant approached philosophy, and it is how we should, too.

IMPORTANT !

Good Will, Goodness and Duty

Moral philosophy of Immanuel Kant is explained in an essay titled Good Will, Goodness and Duty another page. Follow the link below:

Downloadable PDF file is available on this page.

Essay summary:

This essay offers an accessible and comprehensive introduction to Immanuel Kant's moral philosophy, focusing on the concepts of good will, duty, and the categorical imperatives. Kant is presented as a key figure who united rationalist and empiricist traditions, grounding morality not in consequences or feelings but in rational principles.

Kant is asserting that the only thing good without qualification is a good will. Talents like intelligence, courage, or patience are not inherently good, they can become harmful when directed by a "ill" will. Thus, the moral value of an action lies in the intention behind it, not in its outcome. This marks Kant's ethics as deontological rather than consequentialist.

Central to this framework is the categorical imperative, the supreme rational principle that commands unconditional obedience. Its most famous formulation: "Act only according to that maxim which you can at the same time will to be a universal law", requires one to test one's actions by asking whether such action could be universalized without contradiction. Actions such as lying or making false promises fail this test because, if universalized, they would erode trust and undermine the very institutions that rely on honesty.

This essay distinguishes between perfect duties (e.g., not lying, not stealing, paying debts) which admit no exceptions, and imperfect duties (e.g., charity, generosity) which allow flexibility in how they are fulfilled. Kant introduces the idea that rational beings must always be treated as ends in themselves, never merely as means.

Kant's vision of a moral ideal, a "Kingdom of Ends", is explored alongside challenges and criticisms, notably regarding his strict prohibition on lying, even in extreme moral dilemmas such as deceiving "evil doers" to protect innocent lives. Although critics find such rigidity impractical, Kant's defenders argue that his framework provides clarity, universality, and a powerful foundation for moral progress.

The essay concludes by discussing Kant's view of the Summum Bonum, the union of perfect virtue and happiness, which he believes must ultimately be guaranteed by God, ensuring that morality is not futile.

Kant as a person

Disciplined to the point of legend Kant's daily routine was so regular that neighbours joked they could set their clocks by his afternoon walk. This wasn't affectation; it was the outward expression of an inner commitment to order, clarity, and self governance. He believed that a well regulated life supported a well regulated mind.

Physically fragile, mentally formidable

He was small, slight, and often in poor health, yet possessed an extraordinary intellectual stamina. His friends describe him as lively in conversation, sharp-witted, and capable of sudden, sparkling humour-nothing like the austere stereotype that later centuries projected onto him