THUS SPOKE MY OLD MAN !

Welcome to the Idle Words Said in Passing

William of Ockham - a moral dimension

Occam's Razor, - hardly a moral dimension.

He is commonly known for Occam's razor, the methodological principle that bears his name.

One important contribution that he made to modern science and modern intellectual culture was efficient reasoning with the principle of parsimony in explanation and theory building that

came to be known as Occam's Razor.

This maxim, as interpreted by Bertrand Russell, states that if one can explain a phenomenon without assuming this or that hypothetical entity, there is no ground for assuming it,

i.e. that one should always opt for an explanation in terms of the fewest possible causes, factors, or variables. (hmmm, well, this is as clear as mud. )

He turned this into a concern for ontological parsimony; the principle says that one should not multiply entities beyond necessity - Entia non sunt multiplicanda sine necessitate - although this well-known formulation of the principle is not to be found in any of Ockham's extant writings.

He turned this into a concern for ontological parsimony; the principle says that one should not multiply entities beyond necessity - Entia non sunt multiplicanda sine necessitate - although this well-known formulation of the principle is not to be found in any of Ockham's extant writings.

He formulates it as: "For nothing ought to be posited without a reason given, unless it is self-evident (literally, known through itself) or known by experience or proved by

the authority of Sacred Scripture."

For William of Ockham, the only truly necessary entity is God; everything else is contingent. He thus does not accept the principle of sufficient reason, rejects the distinction

between essence and existence, and opposes the Thomistic doctrine of active and passive intellect.

His scepticism to which his ontological parsimony request leads appears in his doctrine that human reason can prove neither the immortality of the soul; nor the existence, unity,

and infinity of God. These truths, he teaches, are known to us by revelation alone.

In science, Occam's razor is used as an abductive heuristic in the development of theoretical models rather than as a rigorous arbiter between candidate models. In the scientific

method, Occam's razor is not considered an irrefutable principle of logic or a scientific result; the preference for simplicity in the scientific method is based on the

falsifiability criterion. For each accepted explanation of a phenomenon, there may be an extremely large, perhaps even incomprehensible, number of possible and more complex

alternatives. Since failing explanations can always be burdened with ad hoc hypotheses to prevent them from being falsified, simpler theories are preferable to more complex

ones because they tend to be more testable.

Whatever happened there throughout the ages the principle of parsimony was well accepted in science and philosophy.

Well, well, this bit was not as exciting as one would hope. Talking of hope, there is something he said that is more amusing and useful. See section below.

The Virtues

Your Hope of Salvation ! Well, maybe, ... read on.

While moral virtue is possible even for the pagan, moral virtue is not by itself enough for salvation. Salvation requires not just virtue (the opposite of which is moral vice) but merit (the opposite of which is sin), and merit requires grace, a free gift from God.

In short, there is no necessary connection between virtue-moral-goodness and salvation. Ockham repeatedly emphasizes that "God is a debtor to no one"; he does not owe us anything, no matter what we do.

For Ockham, acts of will are morally virtuous either extrinsically, i.e. derivatively, through their conformity to some more fundamental act of will, or intrinsically.

On pain of infinite regress, therefore, extrinsically virtuous acts of will must ultimately lead back to an intrinsically virtuous act of will. That intrinsically

virtuous act of will, for Ockham, is an act of "loving God above all else and for his own sake."

In his early work, On the Connection of the Virtues, Ockham distinguishes five grades or stages of moral virtue, which have been the topic of considerable speculation

in the secondary literature:

- The first and lowest stage is found when someone wills to act in accordance with "right reason"-i.e., because it is "the right thing to do."

- The second stage adds moral "seriousness" to the picture. The agent is willing to act in accordance with right reason even in the face of contrary considerations, even-if necessary-at the cost of death.

- The third stage adds a certain exclusivity to the motivation; one wills to act in this way only because right reason requires it. It is not enough to will to act in accordance with right reason, even heroically, if one does so on the basis of extraneous, non-moral motives.

- At the fourth stage of moral virtue, one wills to act in this way "precisely for the love of God." This stage "alone is the true and perfect moral virtue of which the Saints speak."

- The fifth and final stage can be built immediately on either the third or the fourth stage; thus one can have the fifth without the fourth stage. The fifth stage adds an element of extraordinary moral heroism that goes beyond even the "seriousness" of stage two.

So, there you are ... for the heroic you, there is still a hope !

Divine Command Theory

It is believed by many that God commands us, human beings, to be kind. It is believed that kindness is good and that God himself is always kind because his actions are always in conformity with his goodness. This was and still is the most common way of understanding the relationship between God and Morality.

In Ockham's view, God does not conform to an independently existing standard of goodness. He argues that God himself is the standard of goodness. In his view, it is not the case that God commands us to be kind because kindness is good. He asserts that kindness is good because God commands it. Ockham was a divine command theorist: God's will establishes right and wrong.

Divine Command Theory has been unpopular because of its unintuitive implication.

Divine Command Theory has been unpopular because of its unintuitive implication.

If whatever God commands becomes right, and God can command whatever He or She wants, then God could command us always to be unkind and never to be kind, and then it would be right for us to be unkind and wrong for us to be kind. Kindness would be bad and unkindness would be good! How could this be?

In Ockham's view, God has commanded and always will command kindness. Nevertheless, it is possible for Him or Her to command otherwise. This possibility is a necessary requirement of divine omnipotence. God can do anything that does not involve a contradiction.

Many of moral philosophers, such as Thomas Aquinas, insist that it is impossible for God to command us to be unkind simply because then God's will would contradict God's nature.

Ockham would see this as a wrong way to conceive God's nature. In Ocham's view most important element in understanding of God's nature is that it is absolutely free. No constraints to God's will.

For Ockham: All of theology stands or falls with this thesis.

Ockham allows that it is hard to imagine that God should reverse his commands. Yet this is the price of preserving divine freedom. He writes thus:

I reply that hatred, theft, adultery, and the like may involve evil according to the common law, in so far as they are done by someone who is obligated by a divine command to perform the opposite act. As far as everything absolute in these actions is concerned, however, God can perform them without involving any evil. And they can even be performed meritoriously by someone on earth if they should fall under a divine command, just as now the opposite of these, in fact, fall under a divine command. [Opera Theologica V, p. 352]This unconstrained Will of God enables Ockham to make sense of some instances in the Old Testament where it looks as though God is commanding such things as murder (as in the case of Abraham sacrificing Isaac) and deception (as in the case of the Israelites despoiling the Egyptians) and more. But this is, probably not his motive. His motive is to cast God as a paradigm of metaphysical freedom, so that he can make sense of human nature as made in his image.

Many a king waged a war claiming divine guidance, even today, some would be kings still wage wars for purportedly religious reasons.

So, there you go, almost a fudge factor to "justify" a theory. Never mind, even today the Cosmologists and Quantum Mechanics Physicists invent "fudge factors" to explain away the laws of nature and adjust the data to fit their theories.

Contradictions and counter-intuitive conclusions in Theology were always stumbling blocks for most of the faithful, yet, the liturgy always brought them comfort, hope and the renewed faith.

NAVIGATION BAR

The Thinkers Menu!

-

Return to Home Page

Return to Home Page

The Menu Guide to Other Philosophers is on Home Page

William of Occam

(from Latin: Gulielmus Occamus; circa. 1287 - 1347)

Also known as William of Ockham was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, and theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the major intellectual and political controversies of the 14th century. He produced remarkable works in the fields of Theology, Faith and Reason, Philosophical thought, Nominalism, Efficient reasoning, Natural philosophy, Theory of knowledge, Political theory, Logic and more.

A Quote:

The head of Christians does not, as a rule, have power to punish secular wrongs with a capital penalty and other bodily penalties and it is for thus punishing such wrongs that temporal power and riches are chiefly necessary; such punishment is granted chiefly to the secular power. The pope therefore, can, as a rule, correct wrongdoers only with a spiritual penalty. It is not, therefore, necessary that he should excel in temporal power or abound in temporal riches, but it is enough that Christians should willingly obey him.

From a Letter to the Friars Minor" (1334) as translated in A Letter to the Friars Minor and other Writings (1995) edited by A. S. McGrade and John Kilcullen, p. 204.

BUT WAIT, MAYBE ALL IS NOT WELL !

Although he is commonly known for Occam's razor, the methodological principle that bears his name, this actual formulation does not appear in any of his extant works.

While it has been claimed that Occam's razor is not found in any of William's writings, one can find statements such as "Numquam ponenda est pluralitas sine necessitate." William of Ockham - Wikiquote ("Plurality must never be posited without necessity"), which occurs in his theological work on the Sentences of Peter Lombard

We warned you about the vagaries time and of anachronisms.

Phrases such as "It is vain to do with more what can be done with fewer" and "A plurality is not to be posited without necessity" were commonplace in 13th-century scholastic writing (Franklin, James 2001).

BUT WAIT, MAYBE ALL IS NOT WELL !

We warned you about the vagaries time and of anachronisms.

This principle of parsimony appeared much earlier in the history.

Robert Grosseteste, in Commentary on [Aristotle's] the Posterior Analytics Books (circa 1217-1220), declares: "That is better and more valuable which requires fewer, other circumstances being equal... For if one thing were demonstrated from many and another thing from fewer equally known premises, clearly that is better which is from fewer because it makes us know quickly, just as a universal demonstration is better than particular because it produces knowledge from fewer premises. Similarly in natural science, in moral science, and in metaphysics the best is that which needs no premises and the better that which needs the fewer, other circumstances being equal."

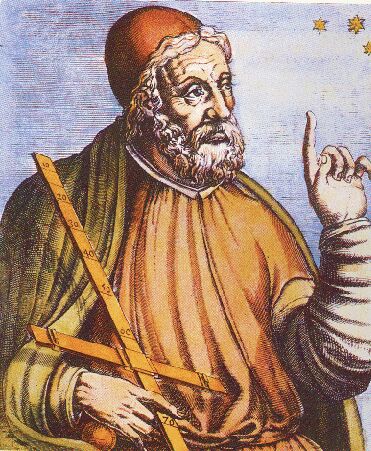

(Claudius Ptolemaeus)

c.100-170 CE)

Also, Ptolemy (90 - 168 CE) stated, "We consider it a good principle to explain the phenomena by the simplest hypothesis possible."