THUS SPOKE MY OLD MAN !

Welcome to the Idle Words Said in Passing

STOICISM - philosophy of happiness!

Practical Thoughts, yet another moral dimension.

Is your life a life of peace and tranquillity ? Do you live in harmony and peace with other people?

We are social animals. We need other people, but, how to live with others without conflict?

Practical Thoughts? Of course, applied philosophy is the way forward. Thinking your way towards The Art of Living well and with Reason.

During the last two and a half millennia many a thinker offered his or her advice and solutions to the problems people faced in their own times. Much of this thinking

and many a solution may have helped people at their own times, but has not endured in its entirety into the future.

One branch of practical philosophy, the Stoicism, and in particular, the ethics part of it, endured and it is as valid today as it was throughout its history.

Let's reflect on historical aspects of Stoicism.

Stoicism was one of the important philosophical movements of the Hellenistic period.

The members of the Stoic school congregated, and held lectures at the Porch (stoa poikilê) in the Agora at Athens. Such was a practice in ancient philosophical

schools,that schools were named by the location where their teaching took place; Epicurean, in the garden, Plato's followers at the Academy, Aristotle. At Lyceum.

Today the English language adjective 'stoical' is utterly misleading with regard to its philosophical origins.

Our phrase 'stoic calm' perhaps encapsulates the general drift of these claims. It does not, however, hint at the even more radical ethical views which the

Stoics defended, e.g. that only the sage is free while all others are slaves, or that all those who are morally vicious are equally so.

(For other examples, see Cicero's brief essay 'Paradoxa Stoicorum'.)

Though it seems clear that some ancient Greek Stoics took a kind of perverse joy in advocating views which seem so at odds with common sense, they did not do so

simply to shock. Stoic ethics achieves a certain plausibility within the context of their physical theory and psychology, and within the framework of Greek

ethical theory as that was handed down to them from Plato and Aristotle.

It seems that they were well aware of the mutually interdependent nature of their philosophical views, likening philosophy itself to a living animal in which

logic is bones and sinews; ethics and physics, the flesh and the soul respectively (another version reverses this assignment, making ethics the soul).

Their views in logic and physics are no less distinctive and interesting than those in ethics itself.

Since the Stoics stress the systematic nature of their philosophy, the ideal way to evaluate the Stoics' distinctive ethical views would be to study them within

the context of a full exposition of their philosophy.

Here we meet with the problem for not a single complete work by any of the first three heads of the Stoic school is extant: the 'founder,' Zeno of Citium

in Cyprus (344-262 BCE), Cleanthes (d. 232 BCE) or Chrysippus (d. ca. 206 BCE). Chrysippus was particularly prolific, composing over 165 works, but we have

only fragments of his works.

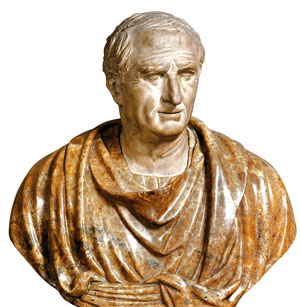

The only complete works by Stoic philosophers that we possess are those by writers of Imperial times, Cicero (106-43 BCE), Seneca (4 BCE-65 CE),

Epictetus (c. 55-135) and the Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121-180) and these works are principally focused on ethics.

The later Stoics of Roman Imperial times, Seneca and Epictetus, emphasise the doctrines (already central to the early Stoics' teachings) that the sage is utterly

immune to misfortune and that virtue is sufficient for happiness.

See below a brief overview of aspects of Stoicism as practiced in Ancient Greece. This overview will be brief, we shall not concern ourselves too much with parts of their doctrines dealing with logic and physics and will with concentrate on the ethics for ethics have stood the test of time. You will find more detailed explanation of ethics on the pages devoted to Marcus Aurelius, Seneca and Cicero.

It is getting complicated ... Go on ... scroll down to next box.

An outline of early Stoic Philosophy.

Following the ideas of the Old Academy, Zeno divided philosophy into three parts: logic (including rhetoric, grammar perception and thought); physics (science, the divine nature of the universe); and ethics, the end goal to achieve eudaimonia through the right way of living according to Nature. Zeno's ideas were developed further by Chrysippus, Cleanthus and others. General views can be outlined as follows:

Logic.

Zeno urged the need to lay down a basis for logic because the wise person must know how to avoid deception. Zeno divided true conceptions into the comprehensible and the incomprehensible, permitting for free-will the power of assent in distinguishing between sense impressions. Zeno said that there were four stages in the process leading to true knowledge .

Physics. The universe, in Zeno's view, is God: a divine reasoning entity, where all the parts belong to the whole. Into this pantheistic system he incorporated the physics of Heraclitus; the universe contains a divine artisan-fire, which foresees everything, and extending throughout the universe, must produce everything: Zeno, then, defines nature by saying that it is artistically working fire, which advances by fixed methods to creation.

This divine fire, or aether, is the basis for all activity in the universe, operating on otherwise passive matter, which neither increases nor diminishes itself. Following Heraclitus, Zeno adopted the view that the universe underwent regular cycles of formation and destruction. The nature of the universe is such that it accomplishes what is right and prevents the opposite, and is identified with unconditional Fate, while allowing it the free-will attributed to it.

Ethics.

Like the Cynics, Zeno recognised a single, sole and simple good, which is the only goal to strive for. "Happiness is a good flow of life," said Zeno, and this can only be achieved through the use of right reason coinciding with the universal reason (Logos), which governs everything. A bad feeling (pathos) "is a disturbance of the mind repugnant to reason, and against Nature." This consistency of soul, out of which morally good actions spring, is virtue, true good can only consist in virtue.

Zeno deviated from the Cynics in saying that things that are morally adiaphora (indifferent) could nevertheless have value. Just as virtue can only exist within the dominion of reason, so vice can only exist with the rejection of reason. Virtue is absolutely opposed to vice, the two cannot exist in the same thing together, and cannot be increased or decreased; no one moral action is more virtuous than another. All actions are either good or bad, since impulses and desires rest upon free consent, and hence even passive mental states or emotions that are not guided by reason are immoral, and produce immoral actions. Zeno distinguished four negative emotions: desire, fear, pleasure and sorrow and he was probably responsible for distinguishing the three corresponding positive emotions: will, caution, and joy, with no corresponding rational equivalent for pain. All errors must be rooted out, not merely set aside, and replaced with right reason.

.jpg)

The "Greek" phase of Stoicism covers first and second periods, from founding the school by Zeno, development of thought by Cleanthes and Chrysippus followed by Zeno of Tarsus and Diogenes of Babylon to shifting of the centre of influence from Athens to Rome. Through Posidonius in the first century BCE a frendship developed with Cicero. Cicero, himself not quite a Stoic in the strict philosophical sense, is one of the best indirect sources about early Stoicism.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, (106 -43 BCE) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher and Academic Skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the establishment of the Roman Empire. His extensive writings include treatises on rhetoric, philosophy and politics, and he is considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the Roman equestrian order, and served as consul in 63 BC.

Cicero studied philosophy under the Epicurean Phaedrus (c. 140-70 bce), the Stoic Diodotus (died c. 60 bce), and the Academic Philo of Larissa (c. 160-80 bce), and thus he had a thorough grounding in three of the four main schools of philosophy.

Cicero offered little new philosophy of his own but was a matchless translator, rendering Greek ideas into eloquent Latin. His other peerless contribution was his correspondence. More than 900 of his letters survive, including everything from official dispatches to casual notes to friends and family.

Borrowing heavily from the Stoic Panaetius, Cicero argues that virtuous conduct is always expedient as well as morally required, and that apparent conflicts between morality and personal advantage are illusory because virtuous action is always the best option.

Since reason "is certainly common to us all," Cicero asserted, the law in nature is "eternal and unchangeable, binding at all times upon all peoples." Cicero warned that it was "never morally right" for humans to make laws that violate natural law. Without laws, Cicero reasoned, there can be no state or government.

On Duties is written as a letter in three parts, focusing on the way that humans should interact with one another in a reasonable manner. It is written this way because Cicero was writing it to his son, who was living in Athens

Nam efficit hoc philosophia: medetur animis, inanes sollicitudines detrahit, cupiditatibus liberat, pellit timores.

For such is the work of philosophy: it cures souls, draws off vain anxieties, confers freedom from desires, drives away fears.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, Tusculan Disputations,

(45 BCE) Book II, Chapter IV;

NAVIGATION BAR

The Thinkers Menu!

-

Return to Home Page

Return to Home Page

The Menu Guide to Other Philosophers is on Home Page

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus

(26 April 121 - 17 March 180 CE) was Roman emperor and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good Emperors and the last emperor of the Pax Romana (27 BC to 180 AD), an age of relative peace and stability for the Roman Empire.

BUT WAIT, MAYBE ALL IS NOT WELL !

Wading through the work of ancient philosophers such as Zeno, Chrysippus and Cleanthes will lead you quietly towards anachronism and, of course, misunderstandings. Most of their beliefs (particularly in science) are not held by many today. Most of those have not stood the test of time. (Although, work of Chrysippus on propositional logic is still quite remarkable.) However, bringing their philosophy to Rome facilitated further development. Romans were very practical people and they introduced further complications with their sense of Duty.

Stoicism is an eclectic philosophy which borrowed heavily from Socratic and Cynic thinkers. Unfortunately, early Stoic practitioners were very much like some Cynics: "holier, more virtuous than thou - in you face" critics of the society. This must have been resented.

Some practitioners, in their zeal, developed "Apatheia" not so much into "equanimity" but more indifference and withdrawal from participation in public life.

Through the introduction of a sense of duty by Romans we can see that this "Cosmopolitanism - all mankind are our brothers and sisters" enabled the kind and generous Caesar Marcus Aurelius to wage bloody wars and kill multitudes of Marcomanni and Quadi with some equanimity.

We warned you to beware of anachronisms.

It is, also, often assumed that the practice of stoic life, by always practicing virtue, is impossible to achieve. Stoics rightly said that it is no harder than practicing Christianity or other religions which practice virtue and condemn sin.

Seneca, marble bust, third century, after an original bust of the first century; in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany. He unexpectedly broke into a smile, or did he?

Seneca, The Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (c. 4 BCE - CE 65), usually known as Seneca, was a Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman, dramatist. As a writer Seneca is known for his philosophical works, and for his plays, which are all tragedies. His prose works include a dozen essays and one hundred twenty-four letters dealing with moral issues. These writings constitute one of the most important bodies of primary material for Roman Stoicism.

More ?

10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23